Tudor Enclosure Movement

After last week’s blog post on enclosure, I felt the need to go back further in time to understand the importance of enclosure in English land policy. I previously mentioned that enclosure first became prevalent during the Tudor dynasty, but failed to provide more context as to “why” and “how.” It is my hope that this second blog post on enclosure will provide a better understanding of this infamous land policy that appeared to have been frequently employed by both the King and Parliament throughout English history.

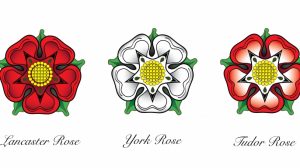

The Tudor family emerged as the victors of the 15th century “War of the Roses,” but they inherited a kingdom that suffered from the aftermath of civil war and economic ruin. Henry Tudor recognized the political polarization of the English royal houses, and thus undertook several notable actions to build a coalition of nobles who would remain loyal to House Tudor. For example, the new king married Elizabeth of House York to merge the two houses together; the same royal house that he fought against and defeated to win the crown. Their unity is symbolically represented by their pair’s royal crest, which appropriates elements from both houses (1825, http://www.thehistoryvault.co.uk/henry-vii-and-elizabeth-of-yorks-marriage-bed-rediscovered/). Guaranteeing the support of his previous enemies was one thing, but Henry Tudor also had to guarantee that the lesser royal houses would not rise up in rebellion against his new regime. The solution? Land grants via enclosure.

The Tudors used enclosure practices to gain the support of noble families. In an agrarian economy where land equated to wealth, families desired large land grants to establish themselves. But the contemporary problem at the time was a lack of available land, because large tracts were held either under monastic rule or by common allocation. King Henry VIII was able to open up more land while undermining the power of the Catholic Church by dissolving monastic lands during his reign. He employed his chief minister Thomas Cromwell to launch a smear campaign against these institutions, and then convinced Parliament to gradually pass legislation that revoked the clergy’s land rights (“The Initial Impact of the 1536 Dissolution,” http://faculty.history.wisc.edu/sommerville/361/361-09.htm). King Henry then appropriated the land to a broad coalition of people who would be likely to support Tudor rule, with the “sale of monastic lands to enterprising and unscrupulous new men–rising courtiers, land-hungry merchants, and the like” (Kines, “The reaction to enclosure in Tudor policy and thought,” p. 3). Enclosure thus seemed to originally began as an auxiliary form of feudalism during the Tudor era, but would later develop into a distinct land policy in itself by the 19th century.

This begs the question as to why Tudor enclosure did not lead to the same degree of demographic change as 19th century parliamentary enclosure did. The best explanation may involve demography itself because the population of England at the time of the Tudors was significantly smaller (2009, http://chartsbin.com/view/28k). When people were evicted from common land during the Tudor era, they could easily find other labor opportunities. In fact, historians estimate that “enclosure was never as widespread as was first thought. Enclosure was most common in the Midlands but only 3% of land there was ever enclosed” (Trueman, “Henry VII And The Economy,” 2016”). Thus, the combined difference in population and amount of enclosure caused Tudor land policy to not have a drastic demographic effect. If anything, Tudor land policy had a larger sociocultural effect as the power of the Church waned at the expense of a new noble class during their reign.

Recent Comments