Response: George Bernard Shaw

Alright, so I’ve taken a relatively long detour but I hope my past research regarding the relationship between enclosure and urbanization establishes some common ground for thinking about the state of the East End slums. As I prepare to move forward with my project, I will try to focus blog posts on a specific individual or group’s response to the Whitechapel murders to show the diversity of opinion.

The Ripper murders occurred within a period of political and social reform. Some of these reform attempts, such as the Contagious Diseases Act of 1864 (which allowed police officers to arrest suspected prostitutes without due process), were certainly not “progressive” by today’s standards. Nevertheless, these attempts reveal a widespread focus by many to reorganize Victorian society into something “better.” This was the age of social change: when leading thinkers sought to challenge the problems which derived from industrialization and urbanization.

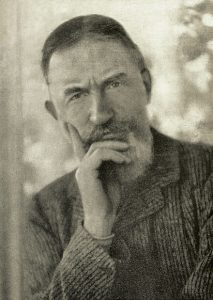

One of these figures was an Irish playwright and political activist named George Bernard Shaw (1911, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Bernard_Shaw#/media/File:Bernard-Shaw-ILN-1911-original.jpg). Shaw was first introduced to political and social thought after attending a lecture by economist Henry George. George was an advocate of equalizing economic rent for natural resources and land titles (ironically, a solution that could have prevented enclosure). Shaw read George’s Poverty and Progress (1881, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progress_and_Poverty#/media/File:Progress_and_Poverty_(1881_edition).jpg), in 1882 and soon began to venture into communist economic thought. These influences led him to develop his own interpretation of socialism, one in which “[it could] be brought about in a perfectly constitutional manner by democratic institutions” (Shaw, Fabian Tract No. 13). Shaw’s “permeation” theory is important because it shows that he retained faith in existing institutions. At a time when many socialist thinkers were advocating for social upheaval, Shaw serves as an example of someone who believed progress could be achieved when institutions and people in power were also invested in change.

It is through these lens that an analysis of Shaw’s April 1888 letter to The Star proves to be an important source in my research of Jack the Ripper’s social legacy. In his letter (reproduced here), Shaw undermines the organizing efforts of the socialist movement by stating, “Whilst we conventional Social Democrats were wasting our time on education, agitation, and organisation, some independent genius has taken the matter in hand, and by simply murdering and disembowelling four women” (Shaw, The Star, September 24 1888). Shaw may be the first person to recognize the social impact of the Whitechapel murders. Historian Paul Begg writes in Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History that “The Ripper wasn’t a social reformer, nor did Bernard Shaw mean to suggest that he was. However, it was recognized then…that the crimes provoked a horrified response from those who had hitherto disregarded or ignored the appeals of traditional reformers” (Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 2-3). Accordingly, a valid argument exists in attributing social and urban renovations within the East End to the Ripper crimes post-1888.

Recent Comments