Response: Charles Booth

During the last few decades of the 19th century, the East End of London became “ground zero” for social reformers. With its high density of working poor citizens, advocates of change published many reports using East End slums as their case studies. While it can not be definitively proved that these treatises are directly correlated to the Ripper murders, a strong argument exists that the crime raised consciousness of the East End’s existence. Negligence and poverty were the previous culprits of these slums; Jack the Ripper just gave a face to them.

Charles Booth was an English social reformer whose work received critical acclaim in the last decade of the 19th century. Booth, educated at the Liverpool Royal Institution (unknown, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liverpool_Royal_Institution#/media/File:Royal_Institution,_Liverpool_1.JPG), challenged government census records on poverty and sought to conduct a more accurate study himself. In 1885, the Pall Mall Gazette reported that “25% of Londoners lived in abject poverty” (Fried & Ellman, Charles Booth’s London, p. 28). Booth worked with several associates to prove that this number was too small; they found that in the East End alone, 35% of residents lived below the “poverty line.”

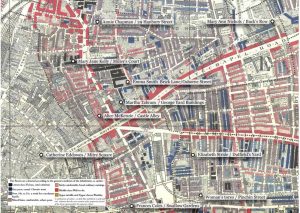

The team’s data and conclusions were published in an 1889 book titled Life and Labor of the People in London (1889, https://archive.org/details/lifelabourofpeop07bootiala). Booth’s most important contributions to the issue were his illustrated maps of the East End. These diagrams, outlined by district, were color coded to show the socioeconomic generalization of every street. The team traveled entire neighborhoods door to door, and published three visual graphics that “represented a combination of factors such as regularity of income, work status and industrial occupation (because some occupations were seasonal and thus irregular)” (Vaughan, Jack the Ripper and the East End Labyrinth, p. 1). Booth used red to denote “well-to-do” urban zones and black to denote “lowest class.” The Whitechapel map (1889, http://www.casebook.org/victorian_london/maps.html) is particularly interesting because there appears to be no homogenous income level, suggesting a wide income gap between rich and poor.

Of course, these maps were created after the Ripper murders, so the serial killer would not have been aware of the quantitative data. But because the canonical murder victims were all found in “chronic want” and “semi-criminal” areas (see below image), one could argue that this prevailing sense of urban stratification was common knowledge. Additionally, some scholars have noted that the physical makeup of the neighborhoods may have enabled the killer to get away and escape discovery. Even Booth recognized in Life and Labor that “physical boundaries such as railways had the effect of isolating areas, walling off their inhabitants and isolating them” (Vaughan, Jack the Ripper and the East End Labyrinth, p. 2). This may explain why three of the five canonical murder victims were found in alleyways.

Charles Booth used his findings to later argue for progressive public policy, advocating for the creation of an “old age pension” system. His color-coded maps continue to be used by historians today, and undoubtedly serve as important primary sources for my research project.

Unfortunately the image that shows Booth’s data overlaying the murder locations is a bit hard to see. I can gladly email a copy of the image as I try to create a larger version!

You wrote, “one could argue that this prevailing sense of urban stratification was common knowledge” – this is the key point of your post, and it is important. Crucial to the historians’ skills is the ability to surmise, to advance upon the factual information in a way that advances knowledge. Even if your common murderer would not have accessed stats, he would know which neighborhoods had the best victims.