Jenny Mackness, United Kingdom

Pedagogy is often defined as the method and practice of teaching, but is that all it is? And what do we understand by teaching? What is a teacher’s role? These are questions that have always engaged educators, but with increasing numbers of learners taking online courses in the form of massive open online courses (MOOCs), teaching online has come into sharp focus again. In my recent reading of research into MOOCs, I have noted reports that there has not been enough focus on the role of the teacher in MOOCs and open online spaces (Liyanagunawardena et al., 2013).

Years ago when I first started to teach online, I came across a report that suggested that e-learning was the Trojan Horse through which there would be a renewed focus on teaching in Higher Education, as opposed to the then prevailing dominant focus on research. It was thought that teaching online would require a different approach, but what should that approach be? Two familiar and helpful frameworks immediately come to mind.

- Garrison, Anderson and Archer’s Community of Inquiry Model (2000), which focuses on how to establish a social presence, a teaching presence and a cognitive presence in online teaching and learning.

Establishing a presence is obviously important when you are at a distance from your students. Over the years I have thought a lot about how to do this and have ultimately come to the conclusion that my ‘presence’ is not as important as ‘being present’. In other words, I have to ‘be there’ in the space, for and with my students. I have to know them and they me. Clearly MOOCs, with their large numbers of students, have challenged this belief, although some succeed, e.g. the Modern and Contemporary American Poetry MOOC, where teaching, social and cognitive presence have all been established by a team of teachers and assistants, who between them are consistently present.

- Gilly Salmon’s 5 stage model for teaching and learning online (2000) which takes an e-learning moderator through a staged approach from online access, through online socialization and information exchange, towards knowledge construction and personal development in online learning.

I have worked with this model a lot, on many online courses. Gilly Salmon’s books provide lots of practical advice on how to engage students online. What I particularly like about this model is that it provides a structure in which it is possible for learners and teachers to establish a presence and ‘be present’ in an online space, but again, MOOCs have challenged this approach, although Gilly Salmon has run her own MOOC based on her model.

In both these frameworks the teacher’s role is significant to students’ learning in an online environment, but these frameworks were not designed with ‘massive’ numbers of students in mind. The teaching of large numbers of students in online courses, sometimes numbers in the thousands, has forced me to stop and re-evaluate what I understand by pedagogy and teaching. What is the bottom line? What aspects of teaching and pedagogy cannot be compromised?

The impact of MOOCS

The ‘massive’ numbers of students in some MOOCs has raised questions about whether teaching, as we have known it, is possible in these learning environments. In this technological age we have the means to automate the teaching process, so that we can reach ever-increasing numbers of students. We can provide students with videoed lectures, online readings and resources, discussion forums, automated assessments with automated feedback, and ‘Hey Presto’ the students can teach each other and the qualified teacher is redundant. We qualified teachers can go back to our offices and research this new mechanized approach to teaching and leave the students to manage their own learning and even learn from ‘Teacherbots’ i.e. a robot.

Is there a role for automated teachers?

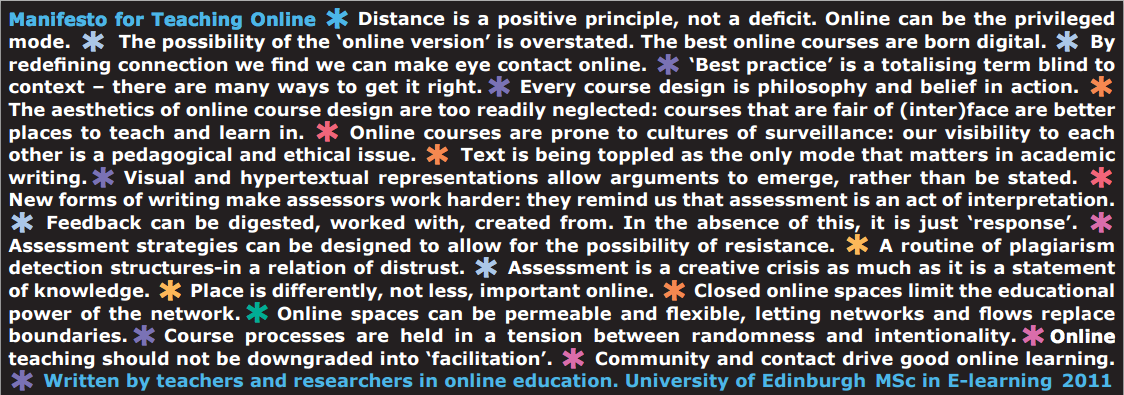

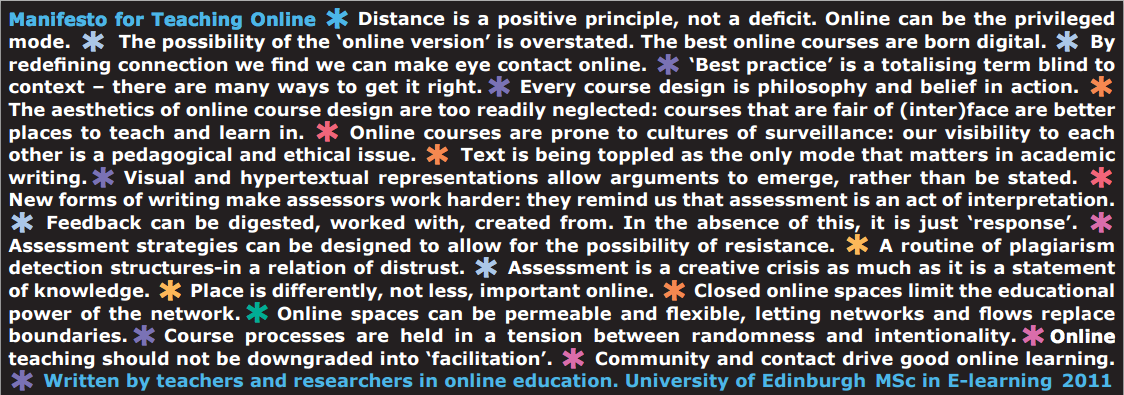

Recently I listened (online) to Sian Bayne’s very engaging inaugural professorial lecture, which was live streamed from Edinburgh University. Sian is Professor of Digital Education at the University of Edinburgh, here in the UK. During this lecture, Sian spent some time talking about the work she and her team have been doing with Twitterbots, i.e. automated responses to students’ tweets. The use of a ‘bot’ in this way focuses the mind on the role of the teacher. The focus of Sian’s talk was on the question of what it means to be a good teacher within the context of digital education. Her argument was that we don’t have to choose between the human and non-human, the material and the social, technology or pedagogy. We should keep both and all in our sights. She pointed us to her University’s Online Teaching Manifesto, where one of the statements is that online teaching should not be downgraded into facilitation. Teaching is more than that.

Sian and her Edinburgh colleagues’ interest in automated teaching resulted from teaching a MOOC (E-Learning and Digital Cultures – EDCMOOC), which enrolled 51000 students. This experience led them to experiment with Twitterbots. They have written that EDCMOOC was designed from a belief that contact is what drives good online education (Ross et al., 2014, p.62). This is the final statement of their Manifesto, but when it came to their MOOC teaching, they recognized how difficult this would be and the complexity of their role, and questioned what might be the limitations of their responsibility. They concluded that ‘All MOOC teachers, and researchers and commentators of the MOOC phenomenon, must seek a rich understanding of who, and what, they are in this new and challenging context’.

Most of us will not be required to teach student groups numbering in the thousands, but in my experience even the teaching of one child or one adult requires us to have a rich understanding of who and what we are as teachers. Even the teaching of one child or one adult can be a complex process, which requires us to carefully consider our responsibilities. For example, how do you teach a child with selective mutism? I have had this experience in my teaching career. It doesn’t take much imagination to relate this scenario to the adult learner who lurks and observes rather than visibly participate in an online course. In these situations teaching is more than ‘delivery’ of the curriculum. It is more than just a practice or a method. We, as teachers, are responsible for these learners and their progress.

The ethical question

Ultimately the Edinburgh team referred to Nel Noddings’ observation (Ross et al., 2014 p.7) that ‘As human beings we want to care and be cared for’ and that ‘The primary aim of all education must be the nurturance of the ethical ideal.’ (p.6). Consideration of this idea takes teaching beyond a definition of pedagogy as being just about the method and practice of teaching.

As Gert Biesta (2013, p.45) states in his paper ‘Giving Teaching Back to Education: Responding to the Disappearance of the Teacher’

…. for teachers to be able to teach they need to be able to make judgements about what is educationally desirable, and the fact that what is at stake in such judgements is the question of desirability, highlights that such judgements are not merely technical judgements—not merely judgements about the ‘how’ of teaching—but ultimately always normative judgements, that is judgements about the ‘why’ of teaching

So a question for teachers has to be ‘‘Why do we teach?” and by implication ‘What is our role?’

For Ron Barnett (2007) teaching is a lived pedagogical relationship. He recognizes that students are vulnerable and that the will to learn can be fragile. As teachers we know that our students may go through transformational changes as a result of their learning on our courses. Barnett (2007) writes that the teacher’s role is to support the student in hauling himself out of himself to come into a new space that he himself creates (p.36). This is a pedagogy of risk, which I have blogged about in the past.

As the Edinburgh team realized, we have responsibilities that involve caring for our students and we need to develop personal qualities such as respect and integrity in both us and them. This may be more difficult online when our students may be invisible to us and we to them. We need to ensure that everyone, including ourselves, can establish a presence online that leads to authentic learning and overcomes the fragility of the will to learn.

Gert Biesta (2013) has written that teaching is a gift. ‘….it is not within the power of the teacher to give this gift, but depends on the fragile interplay between the teacher and the student. (p.42). This confirms Barnett’s view, with which I agree, that teaching is a lived pedagogical relationship. Teachers should use all available tools to support learners as effectively as possible. Pedagogy is more than the method and practice of teaching and I doubt that teaching can ever be fully automated. As teachers, our professional ethics and duty of care should not be compromised.

References

Barnett, R. (2007). A will to learn. Being a student in an age of uncertainty. Open University Press

Biesta, G. (2013). Giving teaching back to education: Responding to the disappearance of the teacher. Phenomenology & Practice, 6(2), 35–49. Retrieved from https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/pandpr/article/download/19860/15386

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Liyanagunawardena, T. R., Adams, A. A., & Williams, S. A. (2013). MOOCs: a systematic study of the published literature 2008-2012. IRRODL, 14 (3), 202-227. Retrieved from: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1455

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring. A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. California: University of California Press.

Ross, J., Bayne, S., Macleod, H., & O’Shea, C. (2011). Manifesto for teaching online: The text. Retrieved from http://onlineteachingmanifesto.wordpress.com/the-text/

Ross, J., Sinclair, C., Knox, J., Bayne, S., & Macleod, H. (2014). Teacher Experiences and Academic Identity: The Missing Components of MOOC Pedagogy. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 57–69.

Salmon, G. (2011). E-moderating: The key to teaching and learning online (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

There is a fine line between “best practices” (meaning some good ideas that you might use), and “college x’s best practices” (the rules which you must follow). The buzz-phrase makes it sound as those these practices have been proven to be “best”, when what’s best is actually affected by instructor personality, discipline, pedagogy, technical knowledge, and other variables. I’ve seen very little agreement on what constitutes what’s best in any sort of teaching, much less online teaching.

There is a fine line between “best practices” (meaning some good ideas that you might use), and “college x’s best practices” (the rules which you must follow). The buzz-phrase makes it sound as those these practices have been proven to be “best”, when what’s best is actually affected by instructor personality, discipline, pedagogy, technical knowledge, and other variables. I’ve seen very little agreement on what constitutes what’s best in any sort of teaching, much less online teaching.