I recently finished responding to three sets of drafts, which is to say, the timing of this first topic is timely. Of course, given who’s facilitating the discussion, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that our first topic of discussion comes at an opportune moment. Thank you, WwM hosts, for this great opportunity to reflect!

What I’m Doing Today – In my online sections, I’ve mainly been using the Canvas discussion board (DB) to assess writing. Specifically, during these past few weeks, I’ve used the board for weekly discussion board questions (DBQs) and essay drafts. I’m also using Google Docs toward the end of the workshop process as a formative tool. How does it work exactly? For each major essay, students complete three formal workshops prior to submitting a final draft. For first drafts, I use the Canvas DB to facilitate the workshop process. I find that it creates a more inviting, less formal space to generate, share, and respond to ideas. Students don’t have to worry about margins, spacing, or other MLA issues. It’s all about ideas, appropriateness, and development–elements I addressed in my response to the question about that which often prompts feedback. In terms of workshop format, since this is a my first time teaching 100% online, I’m keeping things relatively simple. How simple? For the first Canvas DB workshop, students complete two steps:

- Part 1 – Copy and paste the first 1-2 pages of your draft directly into your post. Do not post a link to a Google Doc. Although we will be using Google Docs this semester, you only need to paste your draft into your post for this first workshop.

- Part 2 – Provide feedback to the draft posted before yours by replying to the post and using the following workshop questions. If you are the first to post, you can reply to the draft of your choice. If you are the last to post, I will respond to your draft.

While this approach certainly limits the amount of feedback being received, I think limited feedback is actually beneficial at this early point in the semester because it’s less overwhelming, especially for those new to the workshop experience and/or those less confident in their writing. During this critical part of the semester, I’m far more concerned with easing students into the workshop process, posting drafts and offering feedback, and fostering an online culture and community that is comfortable and constructive. By the third workshop, however, students are posting active links to their Google Docs and offering focused feedback to key passages based on guiding questions and prompt guidelines. So, whereas the first two workshops ask students to post and respond to the Canvas DB, the third workshop asks students to add comments to a Google Doc in addition to providing summative comments as a kind of final reminder for the writer.

In terms of my own role, for the Canvas DB drafts, I’ve been using simple rubrics and providing additional written feedback through SpeedGrader, ultimately working hard, as Warnock notes early in Chapter 11, to immerse myself “textually into the class” (122). (On a related note, visual immersion is also vital, in different ways and moments, hence my modest class photo. It’s designed to give students a big-picture view of their class, an opportunity select a digital seat, and a chance revisit the those elementary school days when class photos were taken.) But back to the topic: To reinforce individual comments, I also provide feedback via announcements and weekly notes. What are these weekly notes of which I speak? Essentially, my Canvas home page, which is designed to mimic smartphone home screen with apps, includes a “Weekly Hints & Notes” section (see upper-right icon with the cookies):

This icon is linked to a Google Doc that allows me to easily address student issues, share excellent examples, drop quiz hints, and provide context for the week. In this sense, the assessment-feedback approach in my online class has looked something like this:

- Post assignment

- Read assignment responses

- Provide specific feedback via SpeedGrader

- Offer general feedback via Weekly Notes

- Post announcement reminding students to check the Weekly Notes

While there’s plenty of room for refinement and utilization of other technologies, what’s nice about this approach in general is how the weekly notes work for both on-ground and online sections. I can utilize the Weekly Notes to address common issues for all of my 100 courses and, in a sense, tie the sections together through common issues. Speaking of tying, to tie back to our text, I also like how this approach allows me find different ways to “respond a lot,” which Warnock recommends “in the beginning of the term especially” (123). Moreover, I was thrilled to hear Warnock address the significance of early responses: “So in week one, if you give students a message board icebreaker to introduce themselves (see Chapter 1), write back a lot. These bits of information place a sharper focus on you as an audience. After a series of responses, you will have given students a snapshot of yourself, and they will be better prepared for the writing ahead” (123-24). Though my relationship with Warnock wasn’t made official until after the start of the semester, we seemed to be kindred spirits with with regard to this aspect. During the first week of class, I began with an icebreaker introduction assignment and spent significant time responding to student introductions by sharing connections and asking questions, all of which has resulted in a dialogue that continues to this day.

Where I Might Be Headed – Given all that Canvas and LTI tools like Turnitin offer, I’m well aware that I’m barely scratching the surface when it comes to assessment tools and feedback approaches. There’s no question I’m primarily relying on written feedback, for instance, to respond to work. Guilty as charged! In the coming weeks, however, I look forward to playing with some of SpeedGrader’s media features and responding to final drafts via Turnitin.

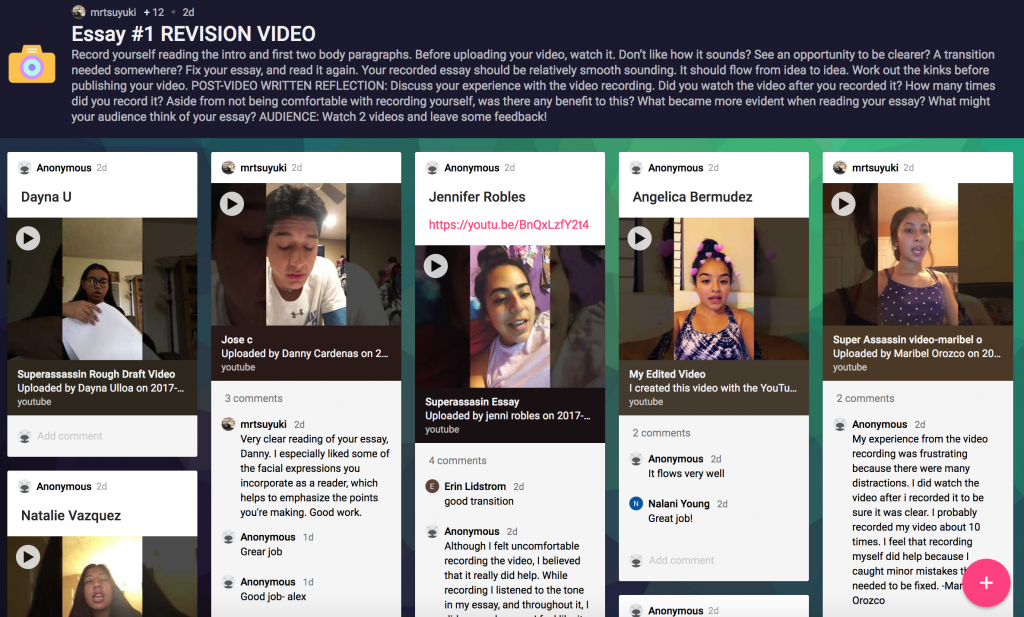

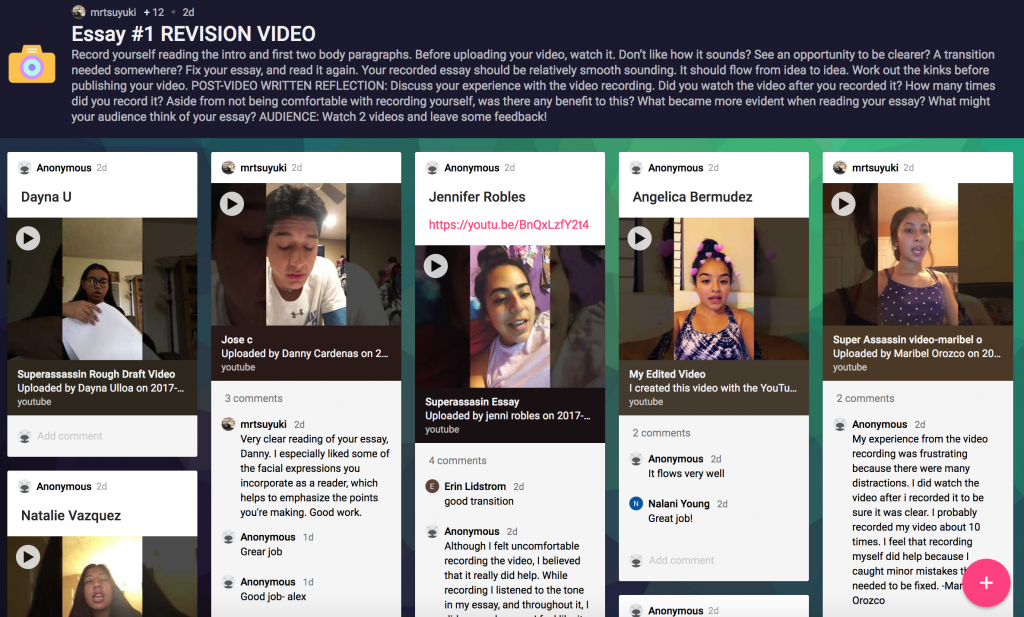

One possibility I’m particularly excited to play with for my second unit came not from Warnock or my Letters colleagues, but from a place a bit closer to home: my brother, Dean, who teaches English at the high school level. Essentially, to assess revisions, he had his students record themselves reading parts of their drafts. Because he doesn’t have access to an LMS like Canvas, he used Padlet and YouTube for the assignment. In his guidelines, he included a few key suggestions: “Before uploading your video, watch it. Don’t like how it sounds? See an opportunity to be clearer? A transition needed somewhere? Fix your essay, and read it again. Your recorded essay should be relatively smooth sounding. It should flow from idea to idea. Work out the kinks before publishing your video.” Here’s how it turned out:

Before I even had a chance to view the Padlet page with the vids, I immediately recognized the value in this kind of formative assessment technique. That is, I recognized how he had found a relatively simple and covert way to get his students to slow down, rethink their ideas, and revise their work. In other words, he was designing effectively based on his audience. He could have said something like this: “Seriously, guys, you need to slow down and reread your work and really ask yourself if these are the best possible words.” Instead, he tapped into the zeitgeist, the essence of specific cultural practices for many of today’s millennials–taking selfies, recording Instagram videos, sharing content on social media–and married it to formal writing. As the reflective comments indicate, many students found the approach challenging yet useful:

- “Although I felt uncomfortable recording the video, I believed that it really did help.”

- “My experience from the video recording was frustrating because there were many distractions. I did watch the video after [I] recorded it to be sure it was clear. I probably recorded my video about 10 times. I feel that recording did help because I caught minor mistakes that needed to be fixed.”

There’s much to say about details like “uncomfortable” and “distracting” and recording a video “10 times,” but I think it’s okay to save those thoughts for a later date. Many students, as we know, have no problem submitting an unbelievably rough draft on which they’ve spent little time. But tie that same draft to social media and suddenly, it seems, students slow down. Now, it’s not just words on a page being shared. Now, it’s words plus them. It’s this “plus them” factor–the innovative tethering of the writer to the work, the packaging of the author with the product–that has great potential. It’s somewhat akin to how I feel about delivering content as a newer online instructor: If I have to post a PP lesson on active vs. passive voice, for instance, no problem. Bring it on! But if I have to turn the same PP into a Screencast-O-Matic lesson that includes my clearly weary, unshaven face in the bottom right-hand corner of the screen, creating and ultimately sharing the lesson takes on a whole new significance. The additional visual element leaves me feeling not so unlike many of many of my brother’s students: uncomfortable and frustrated, yet also more aware and hopefully clearer.

As I consider what’s ahead in my classes, I’m excited about playing with this approach, especially because the media option in Canvas makes it relatively simple for students to generate audio/video content. Soon, my students will be working on the first part of their second essay–a one-page mini argument, in the form of a letter, that’s intended for a specific audience. The brevity of this first part, I think, really lends itself to my brother’s approach. In addition to posting written drafts, students could also post video or audio versions of their essays. Will this new element yield similar results? Will my students find it useful and meaningful? Tediously painful? Bittersweet?

I’ll keep you posted.