Category Archives: Uncategorized

Reimagining My English 202 Online Design

To watch “Reimagining My English 202 Online Design” video, please follow the hyperlink via Canvas.

English 100 Dream Course一Cutting Double Work Time

My future English 100 dream course for my MiraCosta College face-to-face class would focus on having students begin their essays on-site, by augmenting technology use in the classroom. Students would continue to write a Narrative Essay and a Rhetorical Analysis (Essay #1). Instead of having students visit the library or cafeteria to practice the art of narration, by observing and writing about their environment, I want students to tap into their memory and use Chromebooks diligently and begin writing a potential setting, dialogue and characterization . . . they would consider embedding in their narrative essays. (In the past, my English 100 students wrote their practice narrative writing, by writing a free-write entry in their in-class Metacognitive Journal Entries in their Green Books). This new approach would allow students to not waste valuable writing time in the classroom and begin the revision process (since students would receive a grade for this low stakes assignment) before submitting Essay #1. For English 100, to meet MiraCosta College’s elements of research requirement, my students also write a Proposal to Solve a Problem Essay (I moved away from traditional “The Research Paper”); students can focus on any problem at the local, state, national, or global level. For Palomar College, this semester my English 202 students completed a library activity and wrote a paper in a group, and surprisingly the students who worked in a group did better than students who worked alone. I want to adopt the same methodology for English 100. In this dream course, I would encourage students to write a Proposal to Solve a Problem Essay as a community of writers, by sharing research, accessing, and working on the same document, using Google.docs or Word. The semester will end with presentations in the classroom or cafeteria highlighting their solutions一and inspiring classmates and, perhaps, the campus to take action. Lastly, for Essay #3, students write a lens perspective essay, by analyzing a film, Black Panther (2018), Roma (2018), Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018) or a film of their choice, compiling observations, and making connections to their feminist theoretical framework in a Google.docs; the class can access the compilation via Canvas. This approach also allows all students to access in-class work, which can allow them to develop their application paragraphs on their own. For my English 100 Fall 2019, I created a two-page step handout for students to prepare them for Essay #3. The handout requires that students reflect/hand write their potential introduction(s), specifically a lead-in strategy, background information, applications paragraphs, and conclusion(s). While I do believe the handout served its purpose this fall semester, my future students would benefit from typing their notes in their Chromebooks, by cutting the work time and having students record potential responses in preparation for Essay #3. Instead of typing their hand-written answers, students could copy and paste their work from the handout to their essays. These changes in the classroom, I believe, would benefit first-generation college students who have not explored college writing. This English 100 dream course experience would serve as an essential stepping stone tool to write for academia and beyond.

What follows is a list of assignments written for WritingwithMachines 2nd Certificate Sequence, facilitated by MiraCosta College professor, curry mitchell:

Unit 1: Feedback and Assessment: “Warnock Says Professors Can Burn Out from Grading—Good to Know It’s Not All in My Head!”

Unit 2: Collaboration and Group Work Online: “The Power of Community in the Face-to-face and Online Environment”

Unit 3: Equity, Accessibility, and Universal Design: “Teaching in the Time of Socialbots”

Unit 4: Course Design and Organization: “Reimagining English 202’s Online Design”

Teaching in the Time of Socialbots

In Reaching Underserved Students through Culturally Responsive Teaching and Learning in the Online Environment, Dr. J. Luke Wood highlights the “Five Equity Practices for Teaching Students of Color Online.” Professor Wood emphasizes the following practices professors should emulate as online instructors teaching people of color: be intrusive, be relational, be relevant, be community-centric, and be race-conscious. And in “A Position Statement of Principles and Example Effective Practices for Online Writing Instruction (OWI)” allows professors to reflect on principles of universal design and how their online class can facilitate a good online experience and retain students, specifically of color. Luckily, I joined online teaching at a time when Blackboard was fading out and Canvas was being adopted at the 3 out of 4 colleges, where I teach: Mt. San Jacinto College (MSJC), MiraCosta College, Palomar College (CSUSM uses Moodle). Universal design stresses the following: equitable use, technological equality, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for technological error, tolerance for mechanical error in writing, low physical effect, and size and space for approach and use (The Conference on College Composition).

On Being a Metiche (Intrusive)

I learned about being an intrusive/helicopter/metiche professor from Dr. Harris and Dr. Woods’s Teaching Men of Color in the Community College Certificate Program a few years ago, so I now practice this approach in my fully-online MSCJ class and my f2f classes, by emailing students who do not submit a major assignment or students who are missing in action. I also tell students if there is anything I can do to help, writing an email as follows, “Where’s Juan? How can I help you?” Once students reply, I remind students they have my support. My forte is being “a metiche,” nosy. I know that for many students mental stress when they do not talk about their problems and/or mental health problems exacerbate at the end of the semester. I do my best to reach out to potential crisis students to discuss how they can tackle the problem. Another pair of ears from someone like myself allows students to see me as a human being and not a socialbot. At Mt. San Jacinto College, more students experience problems related to poverty, manifesting in mental health. At MSJC and at the San Elijo Campus, students struggled with mental health and suicide. I can reach out via Metacognitive Journal Entries, Canvas email, and my cell phone to ensure I retain students.

Learning to Be Relational

During my first year of teaching (I started teaching in Spain and taught GEW at California State University San Marcos). One day I noticed one of my Latina students was continuously late, and I wanted to address the concern in an upcoming conference. The day of our meeting I noticed her knee was bleeding, so I asked her what happened.

My student confessed she was afraid of me.

I was, obviously, not expecting that response. As the student confided, she fell because she was trying to get to our meeting on time. After much thought, I had many questions and revelations:

- What did someone like me represent to a student (of color)?

- How was she used to seeing women (of color) like me?

- Did I remind her of a grandmother or her mother?

- How was I performing teaching?

- Was I acting like all my English professors who were mostly white?

- Did I want to be perceived as my white “grammar Nazi” professors?

It is at that moment that I began to work on Professor Sonia Gutiérrez being relational and approachable. I believe I am naturally a people person, as a poet professor, I care about people and the world, but teaching throughout my life had been modeled by white professors. Yes, they were knowledgeable, but they were strict, concise, and to the point. (And so was my Mexican father). Luckily for me, I snapped out of it. I am at point where I love teaching, and I love students, and of course, that includes my online students. This year I have returned to feminism, and although one of my fully online male students is experiencing cognitive dissonance, I enjoy the discussions.

Hashtag What? #! LOL

When I first started teaching, the material that I taught got me in the public eye (in trouble). And that was not a good thing for a professor who had just started teaching. It seemed as if everything I wanted to teach was problematic. The Autobiography of Malcolm X aggravated students. According to North County Times article, I was teaching pornography in the classroom, and on top of that I was an unfair grader. I was teaching Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues, Brokeback Mountain, bell hooks’s “Selling Hot Pussy: Representations of Black Female Sexuality in the Cultural Marketplace” among other risqué material. (I, of course, do not have a problem discussing these “controversial topics.”) Because of those early teaching experiences, I decided not to teach Freshman Composition and instead focused on teaching introduction to composition and critical thinking and writing. (I learned a small minority of white male students and Latinos/Chicanos had a problem with the material I selected.) Years later, I have decided to move away from required textbooks and instead do the passionate Sonia. Black Panther through a bell hooks and Du Bois, Roma through triple oppression theory, and Ralph Breaks the Internet through a feminist lens perspective are topics I teach in the class. (Four of my students were published in Tidepools 2019). At MSJC, students do not have to write five papers anymore, so I dropped the research. In retrospect, the material that I select is always relevant and affects my students’ lives and the world as I ask students to analyze topics and encourage students to select their topics at the local, state, national and/or global level.

Community-centric: “We got this!”

A few years ago I learned that if I asked students to work individually I would lose first-year experience students. I, of course, did not want that. Since that revelation, I incorporate a lot of group work. For any material that I wish my students to grasp, I craft a group assignment/paragraph//application paragraph. With the belief that once students work in a group, they will know how to address the assignment on their own. The most important community-centric activity that is the glue of all my composition classes is Whole-class Workshops. My face-to-face students and online students recognize that writing and reading stories are important for their development as critical thinkers and writers.

Through an Equity-minded Race-conscious Lens

Because I was born and raised in the United States, I cannot help but see the world through a race-conscious lens. All the voices in my classes are important, and through their lived experiences, they write narrative essays and rhetorical analyses of their work, analyze popular culture, and reflect on global issues through a problem-solution approach.

Equity-minded Universal Design

For MSJC, I have been teaching for several years now, so I have had an opportunity to explore Canvas.The greatest challenge in online teaching is making sure, online courses are ADA compliant. Next semester, I will be teaching a fully online CS 140: Chicana Thought and Cultural Expression for Palomar College; my goal is to take into consideration tolerance for mechanical error: “Although grammar, mechanics, and usage need to be taught, evaluation should focus primarily on how well ideas are communicated and secondarily on sentence-level errors” (The Conference on College Composition). In writing classes, I do not give As to students who present too many grammar errors and hold my online English students to the same f2f standards. Is that wrong?

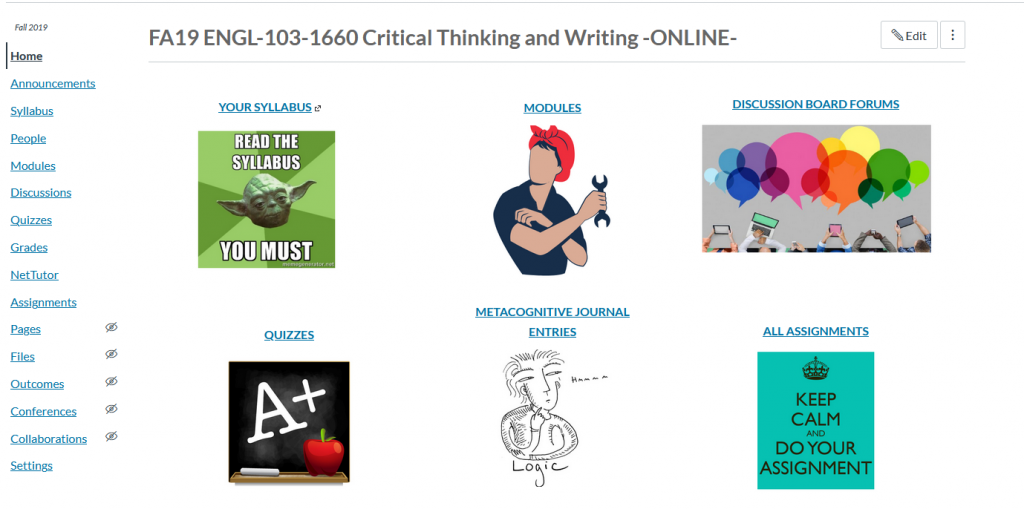

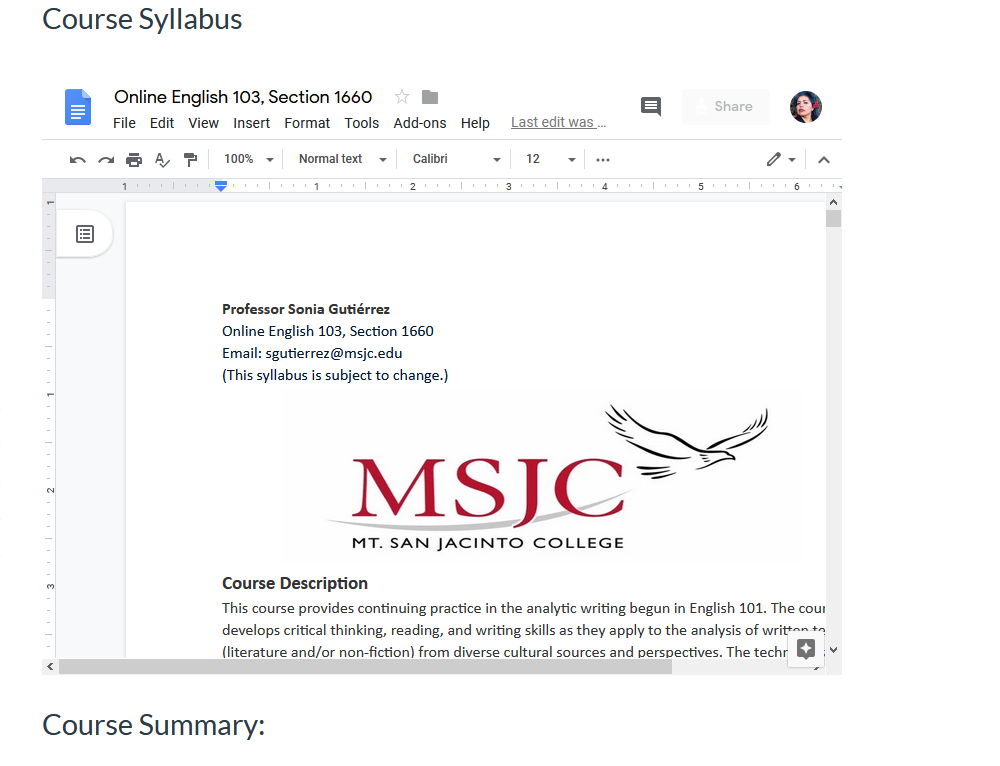

What follow are screenshots of my online classes that, of course, did not look as follows when I started teaching online using Blackboard:

English 103 Home page. All my classes share a similar design.

English 103 Syllabus. All my classes now embed a Google.docs syllabus.

Hybrid English 202 Sample Weekly Announcement. I add weekly announcement every week.

Hybrid English 202 Module. I discovered Headers this semester.

English 103 Sample Unit Overview. My online and hybrid classes include a unit overview every week.

Seq 2 Unit 3: Lessons in Diversity

Wow- Lots of great suggestions in the Wood talk. Here are some I will work at integrating into my curriculum, both online and in on-campus classes:

- Be intrusive: coddling vs net of support. I will provide very generous time and attention to all students, and reach out via email and chat to those who are struggling. I might meet with students on a document or perhaps by skyping (or an equivalent technology) and other synchronous methods that I will explore. Additionally, I will, using Wood’s language, monitor those struggling students’ work and intervene, again, through email or other previously noted methods. Students who may still be on the proverbial fence about college may feel validated and empowered by being recognized by a professor who should speak of the students’ strengths first and then provide support to address the student’s shortcomings in the course, some of which may no doubt be simple time management or other non-academic issues.

- Be relational: Ample office hours, perhaps including an hour or so on the ground and always be available to listen, listen, listen may be key to retaining a student. I like Wood’s reminder that personalized notes via email or on assignments as commentary and feedback make the student feel recognized and valued.

- Be relevant: Here is one of my shortfalls as they relate to texts that reflect the identities of my students of color. Though I have read and love many texts and authors who share these identities, I know I could strengthen the diversity of my texts. I do assign texts by Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, and the film El Norte, I have a way to go to balance my white male-authored texts. Wood makes a note about countering messages that equate race with crime and other negative images. I will try choosing texts that present characters of color as powerful, smart–heroic perhaps. Any suggestions gratefully welcome. I have a few in mind…

- Be community-centric: I like the suggestion about intro videos. If I were a student (the lens I use in planning an online course), I might hate this exercise, but in the end, I would probably really like it. I might ask students to talk a bit about their families’ traditions (if they have said traditions–I acknowledge that some, maybe many, students may not), which could open the door to an introduction that includes ethnic and racial experiences.

- Be race-conscious: I am questionably aware in my on-ground classes that when I have one African-American student, that that student may feel self-conscious if the class discussion turns to race. I do not know if this self-consciousness is a positive or a negative one; I suspect it depends on the student. I’d like to work on being more willing to address the topic of and learn ways to “read” those students of color so that I am not embarrassing them in any way, rather empowering, appreciating, and respecting them. I really like Wood’s suggestion to include images of people of all races and ethnicities in my online course.

- A few other points: monitor microaggressions in Discussion Forums. Have students create memes as part of an assignment. Check out lightboards. Be a great professor.

The Power of Community in the Face-to-face and Online Environment

In “Chapter 14—Collaboration: Working in Virtual Groups,” Warnock writes about the many ways OWCourses can incorporate group work in the online setting. As I mentioned in “Warnock Says Professors Can Burn Out from Grading—Good to Know It’s Not All in My Head!” I am not a fan of peer editing in small groups. I do agree with Warnock when he writes, “a workshop-style can develop” (149) in online classes since that is what I have witnessed in my fully online class(es), where I adopt Ian Barnard’s Whole-class Workshops. When I started teaching online, I knew I would have to figure out a way to migrate my face-to-face Whole-class Workshops activity as a communicative teaching methodology into the online environment.

I learned about Whole-class Workshops during my graduate days at California State University San Marcos when Ian Barnard, professor of Rhetoric and Composition and scholar, visited our campus. Since then, I have adapted Barnard’s approach to the community college student. As a professor, I learned I did not want to deal with excuses: “I didn’t read,” “I was absent,” or “I didn’t get the attachment.” After learning about Barnard’s Whole-class Workshops, I decided my future classes would adopt his methodology but would have to adapt to the needs of community college students: 1) We would have to distribute and workshop student papers on the spot. 2) In pairs using different colored pens, students would learn to diligently read and mark up their peers’ work (for about thirteen minutes). 3) The entire class would provide feedback out loud. 4) Scheduled classmates (the workshoppees) would join the discussion with any lingering questions.

Writing Workshops Face-to-face Approach

For freshman composition and critical thinking and writing classes, I have had to design an approach that works best with my face-to-face classes. What follows is a rough ROUGH outline of my approach to Whole-class Workshops in the classroom:

1. Craft a schedule that includes all the students in the class. (The workshops will take three weeks of the semester. Assign “Adapted from Ian Barnard’s ‘Whole-class Workshops: The Transformation of Students into Writers’ for English 100” at least three weeks in advance. Below you will see a screenshot of a sample Whole-class Workshop schedule. (I used to print out the schedule, but now students can easily access the schedule on Canvas.)

2. For freshman composition courses, introduce students to Ian Barnard’s Whole-class Workshops: the role of the facilitator, the role of the workshoppee (I made this word up), the timekeeper, and critics (Everyone becomes the professor).

What follows is a list of steps I take to familiarize students to Whole-class Workshops and allow them to visualize the class sessions:

- Discuss creative whole-class workshops (during my graduate days creative writing professors used the same model): “Let’s pretend you’re the poet, you’re the novelist . .

- The setup (a large circle). Visually, this large class circle arrangement brings the class together. I always make sure we close the gap and ensure students never give a fellow classmate his, her, or their back if a student trickles in a bit late.

- Tell students about the number of copies they must make (11-14) and being ready (stress accountability). In graduate school, we printed all our classmates’ work.

- Discuss the importance of attendance and participation. (During workshops, I take notes on who arrives late and who responds during the workshop.)

- Discuss the types of questions we will address during Whole-class Workshops.

- Food—writers love treats. We talk about the food we will be sharing and eating during these workshops—Starbuck’s coffee and tamales . . . fruit

- Discuss four memorable unfavorable/strange Whole-class Workshop scenarios (The time a student facilitator’s pupils were dilating (Palomar College), the time a student fainted (MiraCosta College), the time students had a giggle attack (Palomar College), the time a student presented a paper that presented one logical fallacy after another (A long time ago at Palomar College)

- Answer any muddy thoughts about Whole-class Workshops

3. Whole-class Workshop Reflection and Grade

- In my f2f classes, when we conclude our writing circles, students write a Metacognitive Journal Entry about their Whole-class-Workshop experience that includes the students grading themselves.

Fully Online Whole-class Workshops Approach

1. Create a Whole-class Workshop Module (Students read the Whole-class Workshop introductory material at least three weeks in advance), assign “Adapted from Ian Barnard’s ‘Whole-class Workshops: The Transformation of Students into Writers’ for English 103,” introduce students to the Whole-class Workshops Schedule, and assign a Whole-class Workshop Quiz. Below you will see a screenshot of a sample of a fully online Whole-class Workshop schedule.

What follows is a list of steps I must take to ensure we have successful Whole-class Workshops in my online classes:

- Students participate in one Peer-editing Free-write Discussion Board Forum to discuss previous peer-editing experience—positive and/or negative.

- Share a list of questions students can address during Whole-class Workshops.

- For every Whole-class Work Week, I must create 7 to 8 Whole-class Workshop Discussion Board Forums. Students must attach and copy and paste their essay to their designated Whole-class Workshop Discussion Board Forum (In case a student’s paper looks off, students can access the attachment.)

- Students must post their essays by Wednesday, and classmates must critique and reply to their classmates’ essays by Sunday.

2. Online Whole-class Workshop Reflection Assignment

- Students write one Metacognitive Journal Entry about their first Whole-class Workshop experience after the first week of workshops.

3. Similar to a face-to-face class, if students are absent, they get 0 points for participation, and their grade is negatively affected. (Students who test me, meaning, perhaps, if they don’t participate, I won’t find out, write to me right away to inform me they misunderstood the assignment when they notice their grade significantly dropped.) I, of course, allow online students to add their feedback. In my face-to-face classes, as stated in the syllabus, students cannot make up missed Whole-class Workshops.

Whole-class Workshop Failures and Successes

In my few years of teaching online teaching, I have only had three or four memorable negative Whole-class Workshop incidents: 1) The white male student who did not think his fellow Black female classmate should write about racism 2) The white male student who would not address his classmates by name. 3) A female Latina student who claimed in a Metacognitive Journal Entry (private message) her fellow classmates’ feedback was not strong. I responded to the student that, perhaps, it meant she was a high caliber writer; I also shared my not so favorable college peer-editing experiences. Not surprisingly, when it was finally her turn to receive feedback on her paper, her classmates did provide constructive feedback.

Students in my face-to-face class and online classes get to share an essay that they are proud of or a paper that they are struggling with (I do not decide this—this is the pattern I have observed). At the end of each workshop, students leave a workshop with more than a handful of ideas they can apply to their essays (In my classes, revisions are due at the end of the semester). Students comment on how much they appreciated reading their classmates writing styles. Over the years, I have enjoyed being part of these discussions, and judging from students’ body language in my face-to-face classes, they too enjoy Whole-class Workshops since these workshops allow students to grow as writers and thinkers. And students know it!

To Group or Not to Group

Though I don’t use groups very much in my classes, opting often for whole-class discussion after a lesson or to unpack a text (or for any other various reasons), I appreciate their value. I also, of course, understand that synchronous whole-class discussions do not transfer in any practical way in an online format.

From Warnock, “People all over the world are collaborating [online]–why not students?”

Online group project tools for consideration:

- Collaborations (Canvas): I am currently using this tool in my on-round class, and students like it. Creating groups using this tool leads students to a shared Google Doc.

- Shared Google Docs: Simple and familiar.

- Chat rooms: maybe. Unless they were used in an exercise for credit, I’m pretty sure students would find them unnecessary. I made a note, however, below about a possible use for a chat room for conferencing essays.

- Whiteboard: possibly. I’ve only recently worked a bit with this tool, but I would surely consider it.

- Message/Discussion Board: of course. This tool is familiar to most student and it is easy to craft assignments for grading using it.

- Conferences: I am in the process of exploring this Canvas tool for possible synchronous groups. I currently conference in small groups after students have read the essays of three other group members. The five of us meet and discuss those essays in half hour conferences. I may try that exercise using Conference or perhaps Chat Room.

I do like group activities because it nudges otherwise non-participatory students to get involved. In on-ground classes, students can still be silent in groups, but online, they have to add comments if they want to be credited.

Clear, simple instructions and clear roles for group members, maybe rotating on a long-term project. Students would log the work they had done in each role.

In any case, I look very much forward to continued explorations of ways to craft a tightly organized and productive online course that includes group collaborations 🙂

Warnock Says Professors Can Burn Out from Grading—Good to Know It’s Not All in My Head!

Scott Warnock’s “Chapter 10: Peer Review: Help Students Help Each Other,” “Chapter 11: Give Lots of Feedback without Burning Out,” and “Chapter 12: Grading: Should It Change When You Teach Online?” allowed me to reflect on my online teaching, specifically my fully-online English 103: Critical Thinking and Writing” for Mt. San Jacinto College (MSJC) and my hybrid English 202: Critical Thinking and Composition for Palomar College. Critical thinking is a subject I love teaching, but reading Warnock allowed me to ask myself an honest question: Can I improve my online teaching methodologies?

Similar to Warnock, when he writes, “I am an active respondent to my students’ messages” (122), I can’t help myself—I’ve tried not to comment so much. I comment on all my students’ assignments; my comments focus on proving feedback that will allow them to grow as writers and thinkers. As the class progresses, my comments become less and less about superficial errors. Writing feedback does not feel overwhelming (now that I am using an iPad and an Apple pencil).

To be honest, about two years ago I talked to my partner, Paulino Mendoza, to tell him, “Hon, I think I’m going to have to retire from online teaching.” With a concerned look, he asked, “Why?” I explained that providing feedback was draining me. He looked for his iPad and said, “Here, try this.” When I looked at the screen, it was a student’s assignment I could easily write on with an Apple pencil. I wrote a comment as I do for my f2f classes and voilà the stress that made grading unbearable, which I had never experienced in all my years of teaching f2f, went away. With my new magical Apple pencil I began commenting on my online students’ work, and I was happy teaching online for MSJC again. (I’ve only had one student email me a screenshot of my penmanship to ask me what my writing said).

Warnock asks if grading online should change since students do spend the majority of their time in discussion board forums. He writes, “I have found that the informal assignments in my on OWCourse—message boards, peer review, mini assignments need to be boosted to about 30 to 40 percent of the grade” (135). (Participation in Warnock’s OWCourse is 5%—interesting.) Prior to reading “Chapter 12: Grading: Should It Change When You Teach Online?” I had not thought about participation points for an online class. I will reflect on how I will disperse grades in the future since Warnock makes a valid point I will definitely address this coming spring 2020.

What follows is a list of assignments and technology I use to facilitate student learning in my online and hybrid classes:

- iPad and Apple Pencil: To grade Metacognitive Journal Entries, I use my iPad and apple pencil to mark student writing and present constructive feedback when students upload a file. I present prompts that allow students to reflect on their writing and growth as thinkers. (I just discovered I can change the color to aqua blue turquoise. How exciting.)

- Quizzes: To administer Quizzes, I create quizzes using Canvas’s Quiz tools. Similar to Warnock, my quizzes are not difficult at all. Students have an opportunity to take their quizzes two times. Most students receive a 100% on their first try. (Formative Assessments: Syllabus, Chapter Quizzes, Whole-class Workshops, and Graphic Memoir quizzes.) I craft question for #1-4, and students craft their own Q&A for question #5.

- Timed Writing Essay: For MSJC students must write an essay with writing constraints, so I use the same Canvas’s Quiz tools and create a two-hour Timed Writing Essay. (FYI: In my weekly Announcement, I inform students I am not a fan of timed writing tests; however, we must meet the class’s Course Learning Objectives.)

- Whole-class Workshop (Peer-Editing) Discussion Board Forums: I am not a fan of Warnock’s style of peer-editing; however, I do value and embrace Whole-class Workshops in my f2f and online classes. I had horrible experiences as a student: I could give my classmates plenty of feedback, but my classmates could not reciprocate the favor. Sigh. So instead of crossing my fingers that one or two classmates give constructive feedback for a fellow classmate, I use Ian Barnard’s Whole-class Workshops teaching methodology I have migrated to online classes. I prefer Discussion Board Forums for our Whole-class Workshops since they document students work, and everyone learns from each other’s writing. Over the years, I can say I am proud of the writing community I have created in my online classes. I present a Whole-class Workshop Schedule at least two weeks in advance and a list of questions they can address on a fellow classmates’ essays. That means at least twenty-one pair of eyes read and essay and provide constructive feedback.

- Essays: To grade essays, similar to Metacognitive Journal Entries, students upload their essays, and I can now comment on their essay with an Apple pencil. I do truly enjoy reading and commenting this way instead of copying and pasting comments. Ugh.

- Discussion Board Forums: Using Discussion Board Forums, students post formal response papers and free-writes throughout the semester. I also present a Thesis Workshop using Discussion Board Forum (For f2f classes, I use Google.docs to compile the work instead). I sometimes ask student to reply to one or two students. Most students present their work promptly and present their replies in a timely manner. If they do not, I deduct points.

- Writing Group Discussion Board Forums: I attempted a group paragraph using the Canvas tools similar to the ones I administer in the classroom on paper or Google.docs. Epic failure. I ended up telling students the activity would receive credit if they emailed me to request a grade.

- Phone calls: I give students my phone number. If they have any questions about my feedback, they can text me to schedule a phone call.

Feedback, etc.

Thank you for the short video on feedback 🙂

Here’s a few comments on the Warnock:

Ch 10: Peer editing:

I like the guidelines on p. 116

Ch 11: Feedback:

The options I am comfortable with in giving feedback are the following:

- The comment function on Google Docs (yup)

- The use of macros (for sure)

- Rubric software (will explore these)

- Maybe possibly but probably not Turnitin and Quick Mark (I have seen these tools in ‘action,’ and they are often not accurate, at least as the generated comments align with my best assessments)

- When using Google Docs, I may request to meet the student at a specific time to synchronize our interactions re: feedback OR

- Email the Google Doc back with comments within the text and endnotes

- Audio feedback using screencast-o-matic ( I do like the idea of audio feedback. I’d like to hear some comments from colleagues re: students’ reception to this type of response to their work. It seems audio feedback may save some time and work when I don’t have to write comments, though I would probably write comments too: synchronistically in real time, before recording my comments, as I’m recording comments asynchronistically, or some other variation of the listed options- I’ll defer to trial and error at this point or to feedback from instructors who teach online.)

- Meeting f2f

I am open to exploring options, but I like to keep things simple and students probably do too.

WritingwithMachine in Fall 2019

Inspired by the department workshop that Kelly, Jake, Jade, and Tyrone–our HSE colleagues–led in September, those of you who teach composition with technology–either online, hybrid, or onsite classes–within the WritingwithMachines community of practice will develop our own lens on ENGL 100, which we might use to support Project Voltron this semester.

Here’s the plan:

-

Choose a specific composition class you are currently teaching (online, hyrbid, or tech-heavy onsite). Consider the modalities of your course design, texts, and assignments. Think about specific students and their experiences. Reflect on your instructional goals at this moment in the semester. Jot down a few thoughts.

-

Record your thoughts using Canvas Studio and post the video to a discussion board in our WritingwithMachiness Canvas course (see links below).

-

Finally, using Studio’s Comment feature, highlight a moment in your video you’d like your colleagues to listen to and respond.

Participating will require about an hour of work, enough time to organize your thoughts and play around with with one of Canvas’ newest toys: Studio.

There will be three opportunities to participate this semester:

Each time you participate, you can choose which discussion you’d like to join:

- Online,

- Hyrbid

- Tech-heavy Onsite

Since we will collaborate asynchronously in a Canvas, you can participate whenever you have time. Time spent creating, commenting on, and responding to Sound Offs is FLEX eligible. Ultimately, we will use the insights we glean from our Sound Offs to support each other and our students this semester as well as prepare a lens we might bring to Project Voltron when we lead our department meeting next spring.

Thank you again to Tyrone, Jade, Jake, and Kelly for a great September workshop!