For a variety of reasons, I am re-reading John Bean’s Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom (2011).

Early in the text, he offers a definition of critical thinking I hope might provoke some conversation.

Just after admitting that critical thinking methods and practices vary from discipline to discipline, Bean makes an attempt at a broad, cross-disciplinary definition of critical thinking by referencing two mainstays of research in this field: S.D. Brookfield and Joanne Kurfiss (4).

“But certain underlying features of critical thinking are generic across all domains. According to Brookfield (1987), two “central activities” define critical thinking: “identifying and challenging assumptions and exploring alternative ways of thinking and acting” (71). Joanne Kurfiss (1988) likewise believes that critical thinkers pose problems by questioning assumptions and aggressively seeking alternative views. For her, the prototypical academic problem is “ill-structured”; that is, it is an open-ended question that does not have a clear right answer and therefore must be responded to with a proposition justified by reason and evidence. “In critical thinking,” says Kurfiss, “all assumptions are open to question, divergent views are aggressively sought, and the inquiry is not biased in favor of a particular outcome” (2).

I find these ideas about critical thinking intriguing but also quite challenging when I think about how to incorporate them into my teaching (and learning!).

I wonder what your thoughts and reactions are?

Does Brookfield’s emphasis on identifying and challenging assumptions work for you? Do you and your students feel comfortable exploring alternative ways of thinking and acting? (Personally, I would like to think so, but I am not always so sure that I am as courageous as I imagine myself to be on this front!).

What about this idea of ill-structured problems? Does that approach work in your discipline? How have you explored these kinds of problems in your classes and assignments?

And that last clause, “inquiry is not biased in favor of a particular outcome.” What are we to make of that?

I believe I should set up inquiry in my classes that way, but given the realities of assignment design and assessment practices, I sometimes worry I become much more invested in particular outcomes than I am comfortable admitting to myself. Although, apparently, I am quite comfortable admitting this in an email to the whole campus :).

If these questions — or better ones you create on your own — intrigue you (See! No predetermined outcomes here!), consider the following options:

replying to this post on our PDP Joyful Teaching blog (remember, time spent on Joyful Teaching is flex eligible),

or respond to me privately here,

or find some friends wandering campus (perhaps even uncritically!) and lure them into some conversation or inquiry.

Keepers and Loaners

If you would like to explore more about critical thinking, PDP has some first editions of Bean’s book (2001) we would be happy to give away to anyone who wishes to explore and possess forever.

We also have copies of the substantially revised second edition (2011) you can borrow (it includes some good upgrades about more recent research related to critical thinking).

Send me an email or drop by our PDP office if you wish to keep or borrow a text.

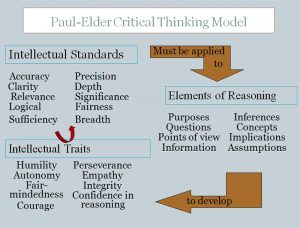

Robert Kelley and The Elder Critical Thinking Framework

Our psychology colleague Robert Kelley has been a leader on campus in promoting conversations about critical thinking. You can check out his resources and work here.

Robert has connected me (and many other colleagues) to the work of Paul Elder, particularly his Critical Thinking Framework. A University of Louisville site has a nice diagram summing up Elder’s ideas, and Elder’s own Foundation for Critical Thinking publishes a very helpful summary of critical thinking related concepts and terms called A Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking. If you follow that link, you will find a truncated “teaser” of the guide, but PDP actually owns some copies of the guide which we would be happy to send along upon request.

Consider exploring Robert’s materials or the Elder Critical Thinking Framework related links I have shared here. Remember, your explorations are flex eligible.

Prepostero

PDP Coordinator

Another side to critical thinking is to believe, not just doubt. When students suspend skepticism long enough to discover, learn, and apply critical thinking lenses or theories to complex phenomena, they are developing a new way of thinking that most often bust their assumptions. I think critical thinking invites wrestling with ideas more deeply, but from both doubt-it and believe-it angles. When I read analysis, I am not just empowered to understand a complex perspective through a theorist’s reasoning, but I am catalyzed to apply my own critical thinking connections beyond the page, the discipline, the issue. We guide our students to question and to understand complex intersections. One way I do this is by guiding them to understand complicated lenses that help them expand their capacities for critical thinking. However, this blog makes me think that my pre-digestion of lenses and texts may be detracting from students’ opportunities to risk and complicate meanings. Perhaps its a balance. I also know this means we should listen to our students with open minds as many are trying out critical thinking for the first time (in academia). Fresh interpretations should be embraced!

“inquiry is not biased in favor of a particular outcome.”

My area of specialization within philosophy is applied ethics. In applied ethics, you apply ethical theory to the facts of the matter in a certain issue to determine what actions are or are not morally permissible (or morally required, prohibited, supererogatory . . .). Almost all textbooks in this field have sections on ethical theory that are separate from the sections on applied ethics, and then try to cover “both sides” of an issue by anthologizing articles that come to different conclusions. I think this makes students think that professional ethicists do what lay people do with moral issues, which is to start with the conclusion you want and use ethical theory to justify it. In reality, ethicists start with the theory, look into the facts of various issues, and come out with a conclusion without their inquiry being “biased in favor of a particular outcome.” Often, that conclusion will make them very uncomfortable. For example, Peter Singer (whose book In Defense of Animals is the foundation of PETA, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) tells the story of how he got involved in the animal rights movement by starting with a disclaimer that he is NOT an animal lover. In fact, he has never had a pet animal. However, he was (and is) a committed Interest Utilitarian. Interest Utilitarianism says that you should act in a way that maximizes the interests of everyone impacted. Friends pointed out to him that his ethical stance should lead him to conclude that, in most circumstances, it would be morally impermissible to engage in animal experimentation or to eat meat. He didn’t immediately accept that, so he began looking into the facts of the matter. Applying Interest Utilitarianism to those facts, he had to conclude that, in most cases, he should be opposing vivisection and factory farming of most animals, because an animal’s interest in not being caused horrible pain is stronger than a human’s interest in having more cosmetics, oven cleaners, veal tenderloin, or eggs. In his investigations, for example, he found that battery hens were often kept so close together in small cages that they had to be debeaked to prevent their pecking each other to death, their feet grew into the wire of the cage so they couldn’t move, lights were kept on 24 hours/day to increase laying, and ultimately this schedule of laying led to painful, prolapsed uterus and an early death. The minimal pleasure he might get from eggs was outweighed by the incredible pain the chickens were put through to produce more of them. Given his ethical stance, he couldn’t justify encouraging factory farmed eggs.

Almost all the moral progress any society or any individual makes starts with this kind of inquiry that emphasizes moral consistency that is unbiased about outcomes. This is easy to see when you look at progress in outlawing slavery, civil rights for women and people of color, . . . It becomes less obvious where taking an unbiased perspective may lead you to culturally uncomfortable conclusions. For example, the latest knock-down-drag-out fight between philosophers was over an article that talked about whether someone could be “transracial,” meaning s/he identified as a race other than the one into which one is born. Often, the facts of the matter are what gets disputed most heavily: does the death penalty deter people from killing? Is race biological or socially constructed, a matter of heritage, upbringing or choice? If we have a policy of allowing assisted suicide, will this lead to people requesting it to avoid being a financial burden on their families?

Critical thinking about ethical issues requires you be unbiased about outcomes of your ethical deliberations, but, at the same time, extremely attached to consistency between your arguments about one issue and another. This is one thing that students have a hard time learning, and even educated adults have a hard time practicing.

What does one do when faced with an ethical argument that is internally consistent but morally reprehensible?

The internal consistency of a single argument isn’t really at issue. The way a student, or really anyone who isn’t versed in ethical theory and applied ethics, generally goes about looking at an issue is to start with the conclusion she or he favors, then try to find an argument that justifies it. If one is very good at constructing arguments, that particular argument may be internally consistent, while the inquiry that led to that argument was completely motivated by a bias about what the outcome of the argument would be. I can create an internally consistent argument for almost any conclusion, and (in fact) — since I teach argumentation as part of ethics (or really any kind of philosophy) — I may have an essay test where students who get test A have to develop an argument in favor of X and students who get test B have to develop an argument against X.

The part of applied ethics that’s so poorly grasped by students and those who make anthologies alike, is that ethicists don’t approach an issue with an eye to the conclusion they’ll reach. It’s the consistency BETWEEN arguments that matters here, rather than the consistency within an argument.

This might be clearer if I talk about something I teach in Epistemology instead (PHIL 101: Intro to Philosophy: Metaphysics and Epistemology). One of the great insights of the Pragmatist philosophers is that “truth lives on a credit system,” as William James says. Which means that we believe whatever we hear first, and only look for justification once we are unavoidably challenged. This leads to a plethora of inconsistencies within our belief system. Most people blithely roll along with the beliefs of their parents, teachers, churches, and televisions, because — another brilliant insight from the Pragmatists — doubt is a very uncomfortable feeling that most people would do anything to escape. As a general rule, there’s an explanation for what people believe, but not really any good reason, nor do they look for one without being pushed into looking for one. It’s not just ethical issues that people decide prior to inquiry, it’s pretty much every belief that they have. The other piece of bad news is that once someone has landed on a belief — even though that belief isn’t based on much — it’s extremely difficult to change that belief with reasons and evidence, AND even when you do change that belief, it only changes that particular belief and not all of the related beliefs that are now inconsistent nor the beliefs they built up on the belief they once had. Recently, there were some experiments about belief revision where they studied people’s reactions to attempts to change their belief on a few issues (e.g. vaccines, GMOs, and climate change). They tried using scientific evidence and using photos and stories that might appeal more emotionally. What they found was that none of that had any effect on what people believe. In fact, some of it had a rebound effect, making people cling more solidly to the original belief. In fact, it’s very hard for people to remember more than one or two times in their lives they’ve ever changed a belief, once formed.

[As an aside, the only thing that did work was making the person feel more secure and confident about him or herself before introducing the new belief. Trump, in my opinion, exploits this tendency well. People on the left only remember him saying “I love the uneducated,” but what he said was “I love the uneducated because they’re smarter and more loyal.” Right there, he’s making people feel good about themselves. They’ve just been complimented, and they’re then prepared to accept new beliefs. If you watch your garden variety political commentator, on the other hand, they start with calling everyone who disagrees with them an idiot, deplorable, cuck, or anything that uses “tard” as a suffix. That provokes instant rejection of that person’s argument, belief, or whatever’s being offered.]

Although, we shouldn’t despair, because people really are disturbed when their beliefs are inconsistent, and if they’re confronted with that (while they are feeling secure and confident), they just might throw themselves into inquiry. One of the really big challenges of teaching is making students feel secure and confident, while at the same time not complacent, so they can safely go into a state of inquiry, including inquiring about the consistency between their beliefs.

I’m annoyed that I didn’t get a notification that you answered me…someone really should talk to whoever’s running this thing…oh…that’s me. 🙂

I did see that study on people’s (un)changing beliefs, and think it has large implications for education in general. It made me think our goal really does have to be critical thinking, rather than changing people’s minds.

Really appreciate your taking time to explain this from the ethicist perspective – I shall focus on the consistency between arguments.

I read one of those studies too, and it was fascinating. Made me think about my own capacity to re-think.

Next to Louisa, I feel like a parakeet. “Hello! Hello! Critical thinking! Hello!” But I’m going to participate anyway, because otherwise I have to work on my syllabi.

For me this topic raises a slew of interestingly maddening questions, starting with: What is the point of teaching people to think critically?

Do we want everyone to think like we do, so “critical thinking” is simply a Trojan horse carrying leftist values like, eg, religious/sexual/ethnic tolerance and environmental protection? (Are those leftist values? Aren’t there tolerant conservatives, Sierra Club Republicans?) Does Singer, in the secret depths of his heart, actually want to persuade us to not eat chickens or not factory farm? Or is he just Expressing His Feelings? Is the person who doesn’t care about chickens an immoral person, or is not caring about chickens just one more perspective?

I find moral/ethical issues really really tricky in the classroom. Humans can’t seem to agree on even the positions I think of as no-brainers: People Are All One Species. Violence Is Bad. No One Needs A Personal Helicopter. Don’t Dump Mercury In The River.

For me, “critical thinking” in the classroom is primitive, focused mainly on rudimentary questions of fact and evidence. To take Louisa’s example, I would ask my students to study at the best available data: do areas with the death penalty (states, nations) have lower rates of crime than areas without it? Can we eliminate other factors that might affect crime rates, eg poverty, addiction, employment opportunities, overcrowding, cultural influences? Are we killing criminals for the purpose of deterrence in the first place, or do we just want revenge? In other words, is the policy based on false pretenses?

I ask students to distinguish between facts and opinion, feeling, belief, custom, wish. I note that human beings are irrational, can’t breathe underwater, and don’t see ultraviolet light. These are just facts, not personal failings or design flaws. We talk about making decisions based on facts as vs. opinion/belief/custom/feelings: what are the benefits? what are the drawbacks? what’s the best way to achieve the goal, solve the problem, make things better? what harm might come? what risks do we take? what does it cost us?

I really should get back to work though.