“My concern is that, even in courses that deliberately design collaborative activities, like Alex’s group project, there appears to be a disconnect between instructor intentions and student experiences. One way to resolve that disconnect is to make collaborative learning an explicit goal that we discuss with our students in OWCs, and an explicit element of our scholarly discussions of Principle 11.”

-Stewart, 2018

Hello all!

This is a challenging topic for me, so I am really looking forward to hearing about some of your own examples with collaborative assignments in your writing courses.

Outside of the one example that Warnock shared about his students working on a team project to develop an argument website, he did not share any other group projects in the online classroom. I definitely believe in collaborative learning, but I have become much more wary about developing high-stakes collaborative writing assignments. I have colleagues who do awesome collaborative projects with Wikipedia Editing, and who have their students go through the online student training platform. I have even participated in such a collaborative writing endeavor on Wikipedia with colleagues. However, I am just not brave enough to go there yet in my classes! I largely remain skeptical about high-stakes group writing assignments because of the many students who often complain that one person does most of the work.

What I have encountered in the past with group papers or assignments is that students are not truly collaborating, and just end up dividing up their work. I am guilty of “the divide and conquer” phenomenon myself when writing with colleagues. I have more recently convinced my co-author of a few articles to start writing individual paragraphs and sentences alongside me in a Google Document instead of our old way of dividing and conquering (she took the lit review and I took the methodology section on some of our quantitative studies because I was the math person). What I found was that the pieces that we “divided and conquered” were not as powerful as compared to when we truly wrote more collaboratively. We worked much better discussing our writing more intimately in a face-to-face setting when we were sitting next to one another typing away and bouncing ideas off one another. I flew back to Macau one summer so that we could finish writing a project together in-person.

Developing collaborative assignments is a complex process. It requires much more than just asking students to jump on a Google Doc and write collaboratively or to respond to their classmates’ ideas in a peer review or discussion forum response. Research supports collaborative learning, but applying it in practice is a challenge!

It’s not surprising that I have been influenced by one of my graduate professor’s research on “Cognitive Presence in FYC: Collaborative Learning that Supports Individual Authoring.” Stewart (2018) found that knowledge construction that resulted from collaborative activities in online FYC courses only took place when the instructor emphasized the value of engaging with multiple perspectives. I continue to value Stewart’s recommendations that group cohesion can be better facilitated when instructors “create activities that invite students to work together toward a common goal instead of co-existing in an online space where they work toward individual goals” (Community Building and Collaborative Learning in OWI). Again, creating that activity with the concept of a “common goal” and “engaging with multiple perspectives” is much easier said than done!

Thus, I would like to second Stewart’s recommendation that students in OW courses and all online courses for that matter discuss the topic of collaborative learning as part of a specific course goal.

Ok, so now I’ll get into the application part of this response! Something that I always do in my on-site courses is a debate related to a reading or topic we are discussing or analyzing. I typically keep the debate as an informal class activity, and I give students plenty of time to prepare for it in class. Students take a position on a topic and move to one side of the classroom to collaborate pieces of evidence from our readings or outside readings that support that position. I typically divide the classroom up into smaller groups of two or three within their position side so that they can have more intimate discussions. Then I ask everyone to stand up and move to opposite sides of the classroom to defend that position. Students can only speak once for their group, and I typically only allow them to speak for thirty seconds to one minute. This goes on for about ten minutes back and forth from each group. Typically, I have students write a response directly after the debate addressing a counterclaim that they heard about during the debate. That piece of writing serves as some type of initial scaffolding for their larger writing assignment (depending on the assignment that they are working on, I’m speaking broadly here—I do this kind of activity in most all of my writing courses regardless of level).

If I were to put this in-class activity online, I think it would work nicely as a low-stakes writing assignment for students. I could ask students to present their initial position or analysis via small groups of 4-5 on one side and 4-5 on another side. That way the discussion forum becomes more manageable. Then I can create a second task where students are required to explicitly use another student’s piece of writing within their response. Warnock suggests that if students are working on a critique that they “account for previous posts in their critiques” (p. 149). The same idea holds true for discussion forum responses in my proposed debate task. Students should build on previous posts by actually acknowledging other classmate’s propositions by writing their classmate’s names, and then building upon their ideas.

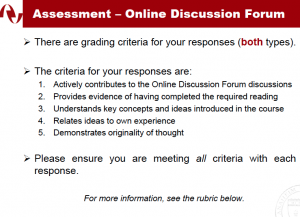

I can’t tell you how many teachers (novice and experienced) struggle with responding to their peer’s ideas my online TESOL education courses. In the first weeks of class, I provide heavy attention and examples of how to integrate a classmate’s ideas into a discussion forum response where students are replying directly to one another. If a student is not using their peer’s names in their response, I almost always send them an e-mail to discuss with them why it is important to include names and why it is important that we collaborate and build on one another’s ideas. I will get students who reply to another peer without writing their classmates name, and who just go on to write about whatever they want to without acknowledging the ideas they are actually responding to. Responding to classmates’ ideas on a forum and extending or adding novel ideas is a process that needs to be taught, modeled, and emphasized within any online course.

What I am learning from my reading adventures this week is that collaborative learning is a topic that should be explicitly addressed with students in any online course, and is a concept that should be addressed early on in a course.

Finally, I’m a musician, and so much about OWI reminds me of the community of practice that most all musicians are exposed to in some form or another. In my own training, I had to regularly attend and perform in masterclasses. I think the masterclass is a great way to envision the community of practice that I imagine my students interacting in.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=14dwegqniNg